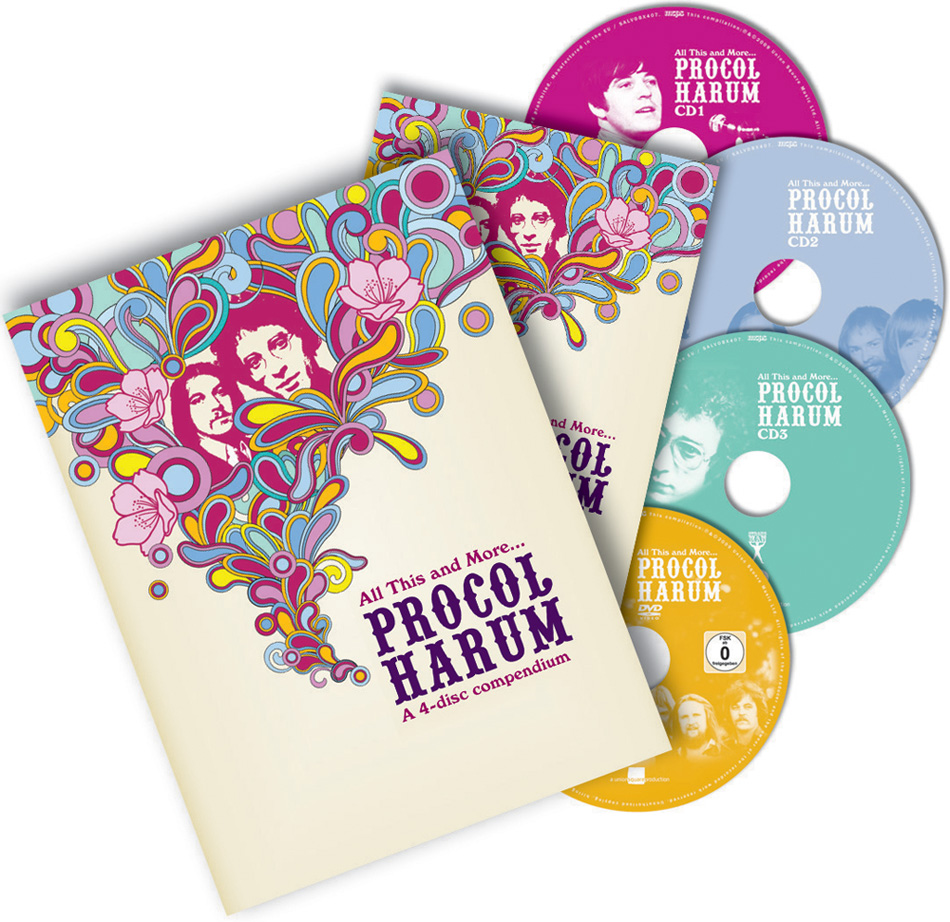

Procol Harum’s recordings have been much-anthologised, but the present ‘audio-visual compendium’ is unique in containing 55% live material, documenting how these unique, moving songs sounded and looked on stage, as a gradually-evolving cast of musicians – nineteen on this compilation – brought fresh stylistic nuances to the cause. It also highlights the material’s enduring quality: every Procol album since 1967 has contributed significant favourites to the touring repertoire.

Patrick Humphries’s survey presents the band in its cultural context; these notes, drawing on the band’s own opinions, focus chronologically on the songs themselves. To date Procol Harum have performed about 110 original compositions (of which 68 are represented here): not a vast catalogue from a partnership founded in 1966. Yet Gary Brooker remains “happy with our output: good songs, not just written for their own sake”.

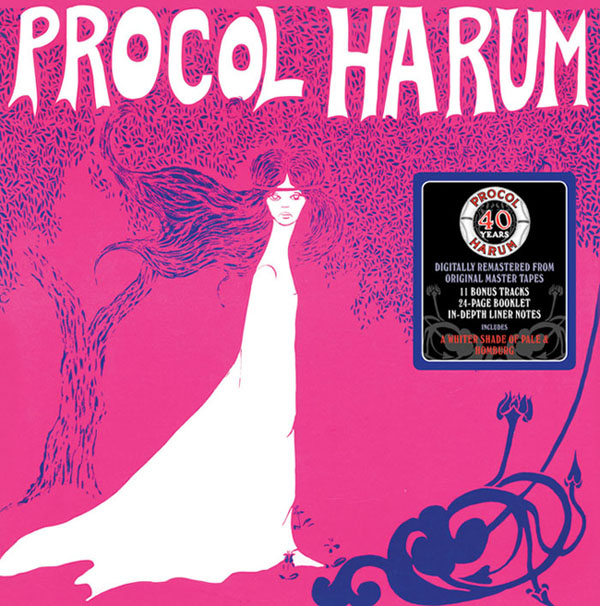

Procol’s 1967

smash hits established the Brooker/Reid benchmark: robustly individual,

plaintively melodic, chord-intensive settings of allusive, witty texts,

majestically yet inventively played. The six million record-buyers who strove to

‘decode’ A Whiter Shade of Pale had only half the story: Keith Reid’s original, typed lyric contains a

third stanza, ‘If music be the food of life...’ (which Gary sings as ‘food of

love’, recalling Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night: he portrayed Duke Orsino at

school and can still recite the famous speech) and a fourth, ‘She said I’m home

on shore-leave...’. These omissions weren’t intended to puzzle: “I never try to

be obscure,” says Keith. “The whole point for me is to communicate. It’s not

that the first two verses were selected: it was overlong; so we just

stopped.”

Procol’s 1967

smash hits established the Brooker/Reid benchmark: robustly individual,

plaintively melodic, chord-intensive settings of allusive, witty texts,

majestically yet inventively played. The six million record-buyers who strove to

‘decode’ A Whiter Shade of Pale had only half the story: Keith Reid’s original, typed lyric contains a

third stanza, ‘If music be the food of life...’ (which Gary sings as ‘food of

love’, recalling Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night: he portrayed Duke Orsino at

school and can still recite the famous speech) and a fourth, ‘She said I’m home

on shore-leave...’. These omissions weren’t intended to puzzle: “I never try to

be obscure,” says Keith. “The whole point for me is to communicate. It’s not

that the first two verses were selected: it was overlong; so we just

stopped.”

Homburg leads with a Jerusalem-influenced figure on the piano, contrasting the début’s sinuous organ; the Whiter Shade descending bassline (Brooker’s homage to Bach) is replaced by an equally ear-catching pedal note, underpinning shifting chords. Top of the Pops fans saw Gary sing at a puny upright, tacked tinfoil on the back; yet they were hearing the weighty grand at Lansdowne Road studios. Both hits remain repertoire staples, Homburg modulating to an emotive climax, and AWSoP boasting several endings (“five,” claims current bassist Matt Pegg) to round off two, three, or occasionally four verses.

The singles’ respective ‘B’-sides hinted impressively at further dimensions: the whirling exuberance of Lime Street Blues and the Vaudevillian Good Captain Clack. Brooker acknowledges the “genre influences” in his earliest compositions; Reid remembers Lime Street as “just a bit of fun, not destined for an album”. Nonetheless it laid Procol’s R&B cards on the turntable (curiously it’s scarcely been played live), convincingly hybridising the young writers’ role-models, Ray Charles and the electric Dylan. Ray Royer and Bobby Harrison, Procol’s original guitarist and drummer, contribute notably to this performance.

But both were gone by the first album: Cerdes (Outside the Gates of) showcases new guitarist Robin Trower and his overdriven Gretsch. Though Trower’s solo sounds carefully crafted, he remembers “going at stuff pretty free-form”, while conceding that “compositional sense is a hallmark of my soloing”. Was Reid’s fantastical imagery chemically inspired? “Totally from my imagination,” Keith declares. “I had never taken drugs when I wrote Cerdes.” Characters like ‘Peep the Sot’ – as with Cerdes, neither specific nor cryptic – belong to a distinctively English nonsense tradition, albeit tinged with Dylan: “I thought he was fantastic!”

Salad Days (are Here Again) is also influenced by 1966’s Blonde on Blonde: “Everybody was,” says Gary. But, born with hungry ears, he searched out unusual chord-changes, ensuring each new song sounded fresh: “Done that one... Let’s think of something else.” For this melody he’d considered another Reid lyric – ‘Take the ice-cream from my shoes...’ – wisely settling on Salad Days. Its ironic title conflates cheery fifties’ musical, Salad Days, with thirties’ favourite Happy Days are Here Again. A headlong, lower-pitched version by the initial line-up – Matthew Fisher’s classy Hammond its chief redeeming feature – was abandoned.

Four Procol albums

conclude with Fisher compositions: in Repent Walpurgis

, a mighty passacaglia on the bassline

of The Four Seasons’ Beggin’, Robin’s guitar explores “a happy

meeting-point between the blues and Procol’s churchy chords”. Newcomer BJ

Wilson’s titanic drumming hints at triumphs to come. Brooker quotes

Tchaikovsky’s first Piano Concerto, and excerpts the first

Prelude from Book I of Bach’s ‘48’.

“Around 17 I’d started teaching myself classical pieces: not reading quickly,

I’d get them by rote, then discard the music.” In 1971 Gary experimented with

the entire Prelude during Repent, which producer Chris Thomas

scored (“turgid and embarrassing,” he now admits) for the Edmonton concert: this

version remains unreleased.

Four Procol albums

conclude with Fisher compositions: in Repent Walpurgis

, a mighty passacaglia on the bassline

of The Four Seasons’ Beggin’, Robin’s guitar explores “a happy

meeting-point between the blues and Procol’s churchy chords”. Newcomer BJ

Wilson’s titanic drumming hints at triumphs to come. Brooker quotes

Tchaikovsky’s first Piano Concerto, and excerpts the first

Prelude from Book I of Bach’s ‘48’.

“Around 17 I’d started teaching myself classical pieces: not reading quickly,

I’d get them by rote, then discard the music.” In 1971 Gary experimented with

the entire Prelude during Repent, which producer Chris Thomas

scored (“turgid and embarrassing,” he now admits) for the Edmonton concert: this

version remains unreleased.

Procol first demoed Conquistador when Andrew Loog Oldham offered them studio time, following a Paul and Barry Ryan session. “It should have been our follow-up to AWSoP,” Keith feels. It proved its chartworthiness with Brooker’s Edmonton orchestration, perhaps the largest-ever cohort to play live on a hit single. In band-only format it has retained elements of Gary’s zestful Hispanic arrangement ever since: Denny Cordell’s flat, mono 1967 mix seems a mere sketch. This Conquistador was recorded at London’s Union Chapel, climax of Procol’s 63-date 2003 tour.

Procol’s eponymous début also contained Kaleidoscope , here interpreted at 2006’s Isle of Wight Festival. The 1967 original has sprouted a rocking prelude: the Hammond’s sustained suspensions build up tension, released in Brooker’s (mildly-garbled) torrent of fractured images. Reid wrote these words for a Jack Smight movie, Kaleidoscope (released July 1966), which Stanley Myers scored: they weren't used. “We encountered Stanley years later at Château Marmont in LA,” Keith remembers. “I’d come a long way from the guy who brought that lyric to his house in Chelsea. He was intrigued that we’d made it.”

Quite rightly so: as a twelve-year-old mod, Reid had professed “no real interest in music”. Like his younger friend Marc Feld (later Bolan) he was attracted by “the clothes thing, being too young for scooters”. Though a library-addict (“My father thought it was pointless buying books when you could borrow them.”) he left Morpeth School unqualified, as soon as legally permissible. The Labour Exchange got him folding dresses in a factory, then navvying on a building-site, “hammering concrete foundations in midwinter, really grim”. Seeking less gruelling work, Keith became a solicitor’s clerk, spending lunchtimes standing in Foyles bookshop, reading “Beckett, Pinter, Osborne, Storey, all the contemporary playwrights”. Songwriting, and his association with publisher David Platz, became his antidote to drudgery. “I wrote a lot of songs in that office off Bloomsbury Square: my ‘Fitzrovia Period’!” he laughs.

Another Isle of Wight 2006 performance – “painfully loud onstage,” in Pegg’s words – Alpha is an early ‘Fitzrovia’ lyric: hence the name. Dating from Olympic Studios’ AWSoP session, it was never officially released. Reid was “trying to write something comical”, predating the freakish humour of the ‘Underground’ cartoonists. “My parents frowned on comics,” he reminisces, “but I had a newspaper round, reading Dandy, Beano, the lot, before stuffing them through people’s doors”. Brooker’s New Orleans-style piano (the sticker commemorates No Stiletto Shoes, his charity-fundraising R&B outfit) builds this revisionist blues – with fluent Hammonding from Josh Phillips, and Geoff Whitehorn’s stalwart Strat – into ‘one circular groove’.

“Procol just look

themselves onstage,” Gary remarks; despite early TV appearances in monkish hoods

(Brooker’s purple, worn down: Fisher concealed in black), “we never had a group

outlook.” They shopped at Dandy’s in the King’s Road: “Matthew was Beau

Brummell-ish; Dave Knights looked like an undertaker. After my black Victorian

shirt…” – the very garment Gary sports in these Isle of Wight clips – “… I

entered a Chinese phase.” Briefly the band (Keith included) was dressed by

Beatles/Cream/Move designers, ‘The Fool’: the collective’s Simon Posthuma

remembers conceiving a “mediaeval rural, but spacey” style for the stage

outfits. “We thought they were quite the ticket,” Trower admits;

much-photographed, they bequeathed Procol a fey, self-indulgent image, quite

out-of-tune with their music.

“Procol just look

themselves onstage,” Gary remarks; despite early TV appearances in monkish hoods

(Brooker’s purple, worn down: Fisher concealed in black), “we never had a group

outlook.” They shopped at Dandy’s in the King’s Road: “Matthew was Beau

Brummell-ish; Dave Knights looked like an undertaker. After my black Victorian

shirt…” – the very garment Gary sports in these Isle of Wight clips – “… I

entered a Chinese phase.” Briefly the band (Keith included) was dressed by

Beatles/Cream/Move designers, ‘The Fool’: the collective’s Simon Posthuma

remembers conceiving a “mediaeval rural, but spacey” style for the stage

outfits. “We thought they were quite the ticket,” Trower admits;

much-photographed, they bequeathed Procol a fey, self-indulgent image, quite

out-of-tune with their music.

Before their second album Procol recorded a single, Quite Rightly So, their first composition co-credited to Fisher. Olympic Studios’ Lowrey organ (a sound Procol revisited in 1975 for The Piper’s Tune) fades in gently... too gently for 1968’s charts. But 2003’s Union Chapel version – Matthew’s last-ever Procol show – swings and storms excitingly, thanks to Mark Brzezicki’s percussive rapport with Matt Pegg, and Geoff Whitehorn’s Fret-King ‘Corona’ 60SP solo. Existential anxiety and wordplay, not psychedelic imagery, are the hallmarks of Reid’s lyric, obliquely lamenting a fractured love-affair; its distorted Romeo and Juliet quotation is poignantly apt.

In The Wee Small Hours of Sixpence was its ‘B’-side. “We didn’t think an awful lot of it,” says Brooker. “The lyric was a bit long for the music.” Keith’s curious title glances at Frank Sinatra’s 1955 album In The Wee Small Hours. Though fans relish the cod-Tennysonian tale of Good Sir Galant, his sword perplexingly ‘blunt as sharp enough’, it’s rarely performed: Gary finds it “tiring to sing, and not one of my best tunes”.

Shine on Brightly , the 1968 album’s title-track, is another matter. “This was moving on in my craft,” Brooker asserts. His potent chord-structures, and the integral bassline devised for David Knights, prompt BJ’s sporadic drum-detonations and Fisher’s most illustrious Hammond playing. Gary sings with passionate melancholy, as Reid’s narrator soldiers through a nightmare wordscape painted in glowing puns and outlandish juxtapositions; engineer Glyn Johns twists the stereo image accordingly. “By this time I’d had psychedelic experiences,” says Keith, “though I always wrote straight”. A guilt-ridden spirituality (perhaps reflecting some Kafka reading) hallmarks his work at this time.

“In the early band the whole atmosphere was one of artistic endeavour, trying to do really good stuff,” Robin Trower remembers. “We were one of the first art-rock bands, forerunners of prog.” Procol’s 1968 masterpiece, In Held ’Twas in I, was indeed covered by prog supergroup Transatlantic in 2000, albeit lacking one of the subsections whose opening words comprise its inscrutable overall title. Procol’s working title, however, was O Magnum Harum, after O Magnum Mysterium, sacred music that Brooker enjoyed on record every Christmas. This brilliantly-ambitious suite (echoed in 1969 by The Beatles’ Abbey Road, side two) intended to “start as small as possible, and end as big as possible”, as Gary puts it now.

“The genesis was that

little exploration about the Dalai Lama,” says Reid. “A lot of people were

thinking about enlightenment at that time.” The oriental instrumentation may be

Zeitgeist-influenced, but Reid’s ‘morass of self-despair’ was worlds away

from pop’s facile hippie credos of ‘a whole generation with a new explanation’.

Procol pre-empt any ‘cringing with embarrassment’ en route to the guru’s

bleakly-comic punchline. “Glimpses of Nirvana

is

not a send-up,” Reid explains. “The Dalai Lama answers the pilgrim with a

question for a question: the question is what’s important.”

“The genesis was that

little exploration about the Dalai Lama,” says Reid. “A lot of people were

thinking about enlightenment at that time.” The oriental instrumentation may be

Zeitgeist-influenced, but Reid’s ‘morass of self-despair’ was worlds away

from pop’s facile hippie credos of ‘a whole generation with a new explanation’.

Procol pre-empt any ‘cringing with embarrassment’ en route to the guru’s

bleakly-comic punchline. “Glimpses of Nirvana

is

not a send-up,” Reid explains. “The Dalai Lama answers the pilgrim with a

question for a question: the question is what’s important.”

Following Gary’s monologue, Keith’s earnest, intimate voice offers the doubt-laden ‘Held close’ intercession; they then trade phrases in the quirky ’Twas Teatime at the Circus (name-checking Reid’s friend ‘King’ Jimi Hendrix) before Fisher’s vocal début on In the Autumn of My Madness . In addition Matthew contributes organ, guitar, glockenspiel, harpsichord and... tubular bells! Brooker’s vocal conquers peaks of passion in Look to Your Soul , where BJ’s cataclysmic punctuations, and Trower’s anguished guitar-break, evoke that ‘life you can’t control’.

“We knew which songs were going where, in terms of making sense,” says Robin, who contributed the proto-metallic riffing, “to flesh it out”, at Gary’s suggestion. Madness is pure Fisher, Soul pure Brooker; they wrote the other sections together. Recorded in various studios (Olympic, De Lane Lea, Advision) on four- and eight-track machines, the suite was expertly assembled by Glyn Johns to sound like a continuous performance. Matthew based Grand Finale (for which Gary’s three-note Rachmaninov bassline paves the way) on Haydn’s Menuet al Rovescio; the recycled Brooker chord-sequence from ‘Held close’ supports Trower’s final, raging solo. Choral singing (including Knights, Reid, Brooker’s wife and Fisher’s sister) concludes the second Procol album on an exultant high.

The overwhelming impression of In Held is of abundant melodic and harmonic invention, tightly-structured song-writing, and thrilling drama in the playing: no ‘sin of self-indulgence’! Archaisms redolent of the pulpit – ‘’twas’, ‘unto’, ‘writ’ – contribute subtly to the overall gravitas. Chris Copping, Procol’s post-Fisher organist, concludes, “This was not an art-rock band, but R&B players lifting their game under the influence of Reidy’s lyrics, astute yet self-effacing, and above all overflowing with sparkling wit. The music all hangs together on that thread”.

Rambling On (California, April 1969) epitomises this line-up’s onstage intensity. “West-coast audiences made a deep impression on me, like another world,” says Trower. His ‘Hubert Sumlin’ sound evolved (“when there weren’t many manufactured pedals around”) by daisy-chaining a ‘Little Giant’ practice-amp with a Fender Twin. After Procol’s first album he traded his Gretsch for the louder Gibson SG: “Nowadays you’d just fit humbuckers... but I was very naïve!” Rambling On was originally even more Dylanesque: ‘By now a crowd had gathered; I replaced my nickel tooth, combed my auburn hairpiece, climbed up onto a roof’. “If I gave Gary something, I usually considered it finished,” says Keith. “But we’d sit at the piano and work together, and sometimes I’d make changes, with singability in mind.”

Seem To Have The Blues (Most All of the Time)

is a Shine on Brightly outtake,

usurped by In Held, but revived by the twenty-first-century band

(“we count it in with ‘One’!” laughs Pegg). This alarming ditty (glancing at

Reid’s early impoverishment) was filmed live in Copenhagen (15 December 2001).

“My approach to blues, being a keyboard-player perhaps, is to use six chords

instead of three,” says Brooker. “It makes for interesting playing, interesting

vocals, interesting solos.”

Seem To Have The Blues (Most All of the Time)

is a Shine on Brightly outtake,

usurped by In Held, but revived by the twenty-first-century band

(“we count it in with ‘One’!” laughs Pegg). This alarming ditty (glancing at

Reid’s early impoverishment) was filmed live in Copenhagen (15 December 2001).

“My approach to blues, being a keyboard-player perhaps, is to use six chords

instead of three,” says Brooker. “It makes for interesting playing, interesting

vocals, interesting solos.”

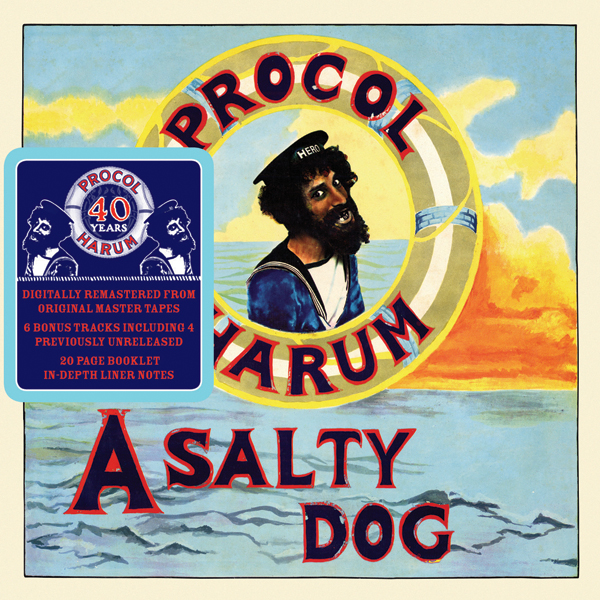

A Salty Dog is the Brooker/Reid song most band-members cite as their favourite. “I was blown away, hearing it with just Gary and piano, at The Stones’ rehearsal-rooms in Bermondsey,” says Robin. Effortlessly composed (“it tumbled from the sky”), its harmonic strangeness remains fresh, its finely-poised melody inspiring. Brooker’s self-taught orchestration – and Fisher’s spacious production (Kellogs, Procol’s roadie, recorded his bosun’s whistle “standing on a chair, to get that sea-going sound”) – made for a classic single: absurdly, it didn’t chart. A short-lived stage arrangement, incorporating an upward modulation, was nixed by BJ: he loved to sing along, and could no longer reach the climactic notes!

The Salty Dog album excellently captures Wilson’s unique drum sound (he personally selected and stretched animal skins for the tom-toms’ lower heads). Its songs inhabit numerous sound-worlds: Gary’s detuned upright on The Milk of Human Kindness was a fixture at Abbey Road Studio 2, used on hits like Side-saddle by Russ Conway (for whom The Paramounts had demoed a backing-track). Though written in America, Milk’s title is Shakespearean, and its ‘wasp without a sting’ is simply an insect metaphor, not a White Anglo-Saxon Protestant.

This album is less Hammond-heavy, except on Matthew’s hymnal Pilgrim’s Progress (with its “AWSoP vibe”, in Copping’s words). Keith feels this was “Procol’s ‘Beatle’ album,” since “whoever wrote the music sang and directed the song”. Reid knew Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress only by title, and Fisher set the lyric because “I shoved it his way”. “I wish Gary had sung it,” Keith adds. “Matthew’s great talents did not lie in that direction.” Fisher’s composition stayed in Procol’s repertoire after he departed.

In this era Trower played a Les Paul Special, “through a brown Gibson amp, second-hand from the Charing Cross Road”: this kick-starts Long Gone Geek , recorded at A&M’s Hollywood studios. More energetic than anything on the Salty Dog album, it was ear-marked for the title-track’s ‘B’-side. ‘Pinstriped Sweet’ (from Cell 15) had been name-checked in Brooker’s Lime Street fade-out: these jail-oriented lyrics are presumably co-eval.

On the Salty Dog album, The Devil Came from Kansas begins in 5/4 (“just for the hell of it,” says Gary). By 11 November 1974, in a Copenhagen TV-studio dressed to resemble a Grand Hotel, the song sports a ‘straight’ introduction, and a hundred-second two-chord workout quite unlike anything Procol had recorded. Wilson’s rhythm-bridge is characteristically unpredictable: “I’d stamp, four to the floor, to keep my place,” Copping confesses. “You picked up BJ’s angle unconsciously,” adds Mick Grabham, “like getting to know a particular broadsheet crossword”. Brooker habitually ‘localised’ Reid’s lyric: here ‘Kansas’ becomes ‘Carlsberg’, the cheese ‘Danish Blue’.

Another Salty perennial is the first Trower/Reid song, Juicy John Pink (its title a lubricious cousin of Jumping Jack Flash, its music a pared-down descendant of Muddy Waters’s John the Conquer Root). Recorded at the huge, third Isle of Wight Festival (28 August 1970) this late-night romp spices up the lean album arrangement, taped at The Rolling Stones’ studio: rocking piano, bass and drums recall the Paramount fodder that Procol liked to serve for encores.

All This and More

, from the Edmonton

album (18 November 1971), restores Brooker string-writing omitted by Fisher from

the Salty mix. Newcomer Alan Cartwright’s Fender Precision takes the

ingenious scalar bassline; Trower-replacement Dave Ball’s Gibson SG

verse-embellishments are suitably mellow. Yet Ball’s Marshall rig had burnt out

during the first orchestral rehearsal; an “awful Ampeg combo” replacement

“lasted about an hour”. Another Ampeg was finally procured and “though I

twiddled the knobs to a reasonable-looking setting,” says Dave, “I didn’t

hear it until our opening number. Did I mention the gig was fraught?”

All This and More

, from the Edmonton

album (18 November 1971), restores Brooker string-writing omitted by Fisher from

the Salty mix. Newcomer Alan Cartwright’s Fender Precision takes the

ingenious scalar bassline; Trower-replacement Dave Ball’s Gibson SG

verse-embellishments are suitably mellow. Yet Ball’s Marshall rig had burnt out

during the first orchestral rehearsal; an “awful Ampeg combo” replacement

“lasted about an hour”. Another Ampeg was finally procured and “though I

twiddled the knobs to a reasonable-looking setting,” says Dave, “I didn’t

hear it until our opening number. Did I mention the gig was fraught?”

There’s a Crucifixion Lane in South London, and Reid “had a bit of fun” changing its spelling for this unjustly-neglected Salty title (like the later Memorial Drive, it has overtones of Dylan’s Desolation Row). Trower had composed “in an Otis Redding vein, like I’ve Been Loving You So Long... but Keith was a bit of a misery with the words!” (“A very confessional lyric for me,” Reid confides). Robin’s vocal founders in the instrumental storm towards the end of this Crucifiction Lane from California (April 1969), which otherwise follows the recorded template. Gary’s own setting of the words, “submitted a bit late”, has never been heard.

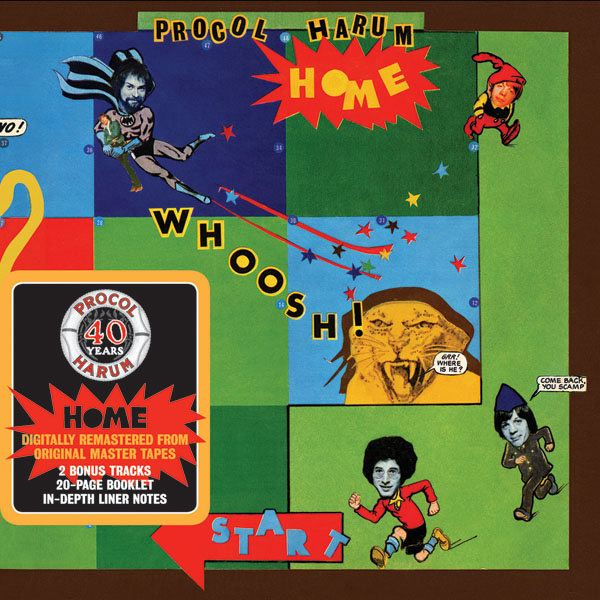

1970’s Home album saw several changes. Chris Thomas, despite his White Album Beatle credentials, “felt very green” when Gary invited him to produce a band whose “last album was so fantastic”. Thomas recollects Brooker’s rejoinder: “We’re not doing a follow-up to Salty Dog, just the next Procol album.” Reid was racked with doubts: “Am I going to be able to write any more songs?” Summoning the necessary passion to sing Keith’s harrowing Still There’ll be More , Gary pounded his Paramounts-era Pianet (unplugged) until it disintegrated. Chris Copping was new and enthusiastic, doubling organ and Ampeg bass. “We attacked these organ-free songs in post-Paramount fashion,” he recalls: “Procol became a band that sweated.”

The bedrock of About to Die is Trower’s Les Paul – “those changes had real drama,” he declares – playing through a Leslie (hot from McCartney’s Maybe I’m Amazed guitar overdub); Brooker uses two Binson Echorecs, triggered live, for piano-echo. Atypically the piano takes the solo: equally unusually Reid’s contribution (“about a loving, New-Testament God”, he says) postdates the tune.

Chris Thomas’s first Procol session yielded Whisky Train (live to two-track) and Barnyard Story (late-night eight-track). “The band left, and Gary sang it at the piano. I said ‘stood upon a lamp-post’ was a great line, and Keith’s voice came out of the darkness: ‘It’s “Olympus”, actually.’ He was there for every recording.” Brooker loves Barnyard (“a proper song”), recalling “the excellent piano sound in EMI studio 2”. He overdubbed upright bass (“my début, very exciting”), and Copping added Hammond. “We tried different approaches and settled on the very simple,” says Chris. “I was no Matthew, but there was good chemistry.”

The false start on Your Own Choice (Trower testing his Leslie over Brooker’s sprightly piano: “We kept it, just for fun,” says Gary) reminds us how Procol recorded rhythm tracks live, irregular half-bars and all. Copping (admirer of American bassists, from Sly to Motown’s Jamerson and Babitt) and Wilson provide a springy synergy. Copping considers this “the best-recorded track on Home: Robin’s rhythm-playing is masterful”. Reid’s relative levity, still morbid, epitomises “a dark album... I didn’t find writing these easy”. Session-man Harry ‘Groovin’ with Mr Bloe’ Pitch – not Larry Adler, as some commentators claim – ends the show with fine chromatic harmonica.

Home

opener Whisky Train was driven by BJ’s demented cowbell and Robin’s

guitar riff; keyboard involvement was minimal. The words (to which Brooker gave

twice the rhythmic space they’d occupied in Reid’s original, hoedown-like

conception) seem unusually worldly, and the song has endured: Gary featured it

with Ringo’s All-Starr Band in the nineties. 2007’s exciting rendering

(Turin, 29 November) sees new drummer

Geoff Dunn “off the leash – I just launch in, unmapped”, he says. He’s mindful

of BJ’s legacy, yet “Gary is open to any input: he wants you to contribute

creatively.”

Home

opener Whisky Train was driven by BJ’s demented cowbell and Robin’s

guitar riff; keyboard involvement was minimal. The words (to which Brooker gave

twice the rhythmic space they’d occupied in Reid’s original, hoedown-like

conception) seem unusually worldly, and the song has endured: Gary featured it

with Ringo’s All-Starr Band in the nineties. 2007’s exciting rendering

(Turin, 29 November) sees new drummer

Geoff Dunn “off the leash – I just launch in, unmapped”, he says. He’s mindful

of BJ’s legacy, yet “Gary is open to any input: he wants you to contribute

creatively.”

The Home-era four-piece Procol had to swap bass duties when organ was required. On quiet songs, Robin played bass: on guitar-oriented pieces, Chris doubled on a 32-key Fender bass keyboard, which hampered his Hammond registration and Leslie changes. Danish TV’s Piggy Pig Pig demonstrates the five-piece potential of this chromatic rocker (“a bass player’s favourite”, says Pegg). Matthew Fisher suffers a strangely-sited Leslie switch, while elaborating organ lines written by Gary for Keith to play on Home. Reid’s lyric (concerning “a harsh, Old-Testament God”) included no farmyard chanting: a studio creation, it underlines a frequently-recurring Procol rhythm.

Unusually, Brooker and Reid wrote the epic Whaling Stories together, planning “a mini In Held, but all played in one go”. Keith feels it’s “like a voyage, though there’s no sea imagery”. “It’s Turner meets Conrad meets Blake,” says Copping, “a chef d’oeuvre: Gary did a mighty job with such a monstrous poem”. For Trower “its emotional content pushes the button”. Home’s eight-track arrangement was fleshed out for Edmonton; Brooker’s orchestral parts, subsequently lost, were aurally recreated by David Firman, who conducts Whaling Stories , live at Ledreborg Castle (20 August 2006) with Denmark’s UnderholdningsOrkestret and Radiokoret.

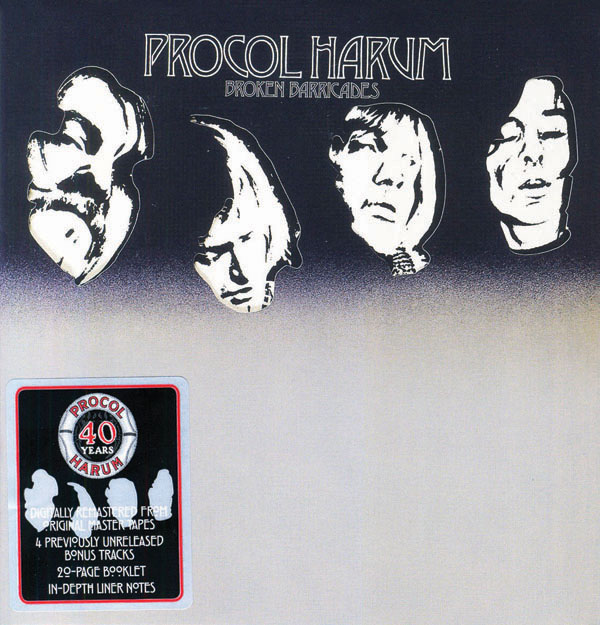

Chris Thomas’s production flair blossomed on Procol’s next offering: he cites the influence of Phil Spector, under whom he’d played (uncredited synth) on George Harrison’s All Things Must Pass album. Sixteen-track technology undoubtedly helped: on Broken Barricades Thomas used outside guitarists (including Tony Duhig from Jade Warrior), to double Gary’s left-hand piano; Trower features only in the playout feedback, alongside Brooker’s glittering Moog. Wilson’s superb performance is captured in appropriate detail (engineer John Punter was a drummer himself). The middle-eight makes for an unusual Procol song, which “could have done with more words”, says Gary now. Keith rethought the ‘dead daughters’ (originally ‘dead babies’): “I was thinking of Egyptian plagues, the dead firstborns…” (Exodus 11 v5). And the ‘stations’ are Stations of the Cross: “It’s apocalyptic, a civilisation dying, enemies coming out on top.”

As with the thematically-related Conquistador, these words inspired sparkling orchestration from Brooker: with a rejigged line-up, Broken Barricades was a highlight of Procol’s Hollywood Bowl concert (21 September 1973) with the LA Philharmonic and Roger Wagner Chorale (whom Gary specially admired, scoring a six-carol medley for their Christmas Camel introduction).

The Barricades album, like Home, opens with heavy guitar: Robin

starts Simple Sister on Les Paul, switching to Fender Strat (keystone of

his subsequent solo career) for what he calls “the thematic riffing”. Brooker’s

arrangement (originating on 1995’s The Long Goodbye symphonic Procol

album) incorporates some of Trower’s improvisations, making the Ledreborg

Simple Sister

a fascinating hybrid; the original’s “heavy metal” (represented by

Whitehorn’s Fiftieth-Anniversary Strat) commingles with impressionistic, exotic

timbres in the orchestral writing. Tremolo string-playing replaces 1971’s

speeded-up piano chattering in the instrumental build-up (its riff related to

The Capitols’ 1966 Cool Jerk). Brazen final discords echo the lyric’s

brutality.

The Barricades album, like Home, opens with heavy guitar: Robin

starts Simple Sister on Les Paul, switching to Fender Strat (keystone of

his subsequent solo career) for what he calls “the thematic riffing”. Brooker’s

arrangement (originating on 1995’s The Long Goodbye symphonic Procol

album) incorporates some of Trower’s improvisations, making the Ledreborg

Simple Sister

a fascinating hybrid; the original’s “heavy metal” (represented by

Whitehorn’s Fiftieth-Anniversary Strat) commingles with impressionistic, exotic

timbres in the orchestral writing. Tremolo string-playing replaces 1971’s

speeded-up piano chattering in the instrumental build-up (its riff related to

The Capitols’ 1966 Cool Jerk). Brazen final discords echo the lyric’s

brutality.

Trower used four economical chords – and “a great riff” according to Copping – for Memorial Drive. He didn’t sing it (“it lent itself to Gary’s voice”) and, as with his About to Die, Brooker’s piano took the solo; yet, Robin told me, “I had plenty of space, and never felt I was kept out of the limelight”. Twenty-first-century Procol extend the song , an impromptu addition to their Danish TV setlist: it’s driven by Whitehorn’s Fret-King ‘Corona’ 60HB, while Brzezicki’s playful fills pay creative homage to BJ Wilson.

Dead daughters, simple sisters, Zulu queens, oyster girls: Reid denies that Procol albums are deliberately thematic, while acknowledging his writing’s unconscious undercurrents. The ‘steaming vat’ of Luskus Delph “doesn’t leave much to the imagination” according to Gary: he gave it a tenderly romantic melody, “since sex is a thing of beauty”. The intriguing title (perhaps mating ‘luscious’ with ‘suck’, ‘demon’ with ‘elf’?) provides “a suggestion of eroticism without being too explicit”, Keith explains. This decorous Edmonton performance (brass replacing Brooker’s original Moog) was the hit Conquistador’s ‘B’-side.

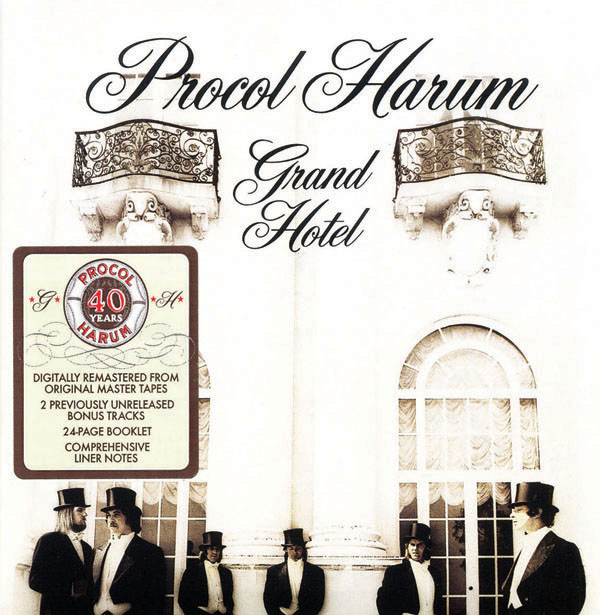

“When Procol did something that worked well, we’d decide to do the exact opposite next time,” says Keith Reid. “After our success with orchestra on Edmonton, we wanted to pare Grand Hotel down to basics.” From 1972 his work did become more direct, if no less evocative; Brooker’s did not. A Rum Tale (“my best waltz ever”) features a capricious, challenging chord-progression under the sweetly unforced melody. Gary calls it “a natural song, not thought-about in any way”, though “the verse needed more words: the chorus arrives too early”. Despite any perceived imperfection, this alcoholic’s reverie is a favourite among fans and band-members alike.

Chris Thomas had just produced John Cale’s Paris 1919, rife with experimental sound-combinations. “Procol were very encouraging, giving me free rein,” he reminisces. For Liquorice John was recorded with incoming guitarist Mick Grabham’s Vox AC30 ‘exciting’ the piano-strings while bricks jammed the sustain-pedal down; harmonium and varispeeded ‘chorusing’ completed the watery ambience. BJ’s explosive drumming offsets Gary’s plangent chording and metrical irregularities. Reid’s words commemorate the suicide, by falling, of Southender Dave Mundy (who had nicknamed Brooker ‘Liquorice John Death’). They’re also personal: “Like a million people I knew Stevie Smith’s Not Waving, But Drowning, but I myself nearly drowned, swimming somewhere with Procol. Far out, in trouble, I was saying ‘help me’... They thought I was just waving.” An apparent title-pun (‘Fall Icarus’?) is wholly undeliberate, Keith adds.

“From light-heartedness to Gothic angst,” is Copping’s assessment of Robert’s Box , “the downside of too many substances”. Reid had The Beatles’ own ‘Dr Robert’ in mind, and Chris remembers pre-tour “trips to 77 Harley Street... the waiting-room was a rock’n’roll lounge”. Brooker’s goofy basso is varispeeded; the ‘aloha’ backing-vocals evoke his father’s band, Felix Mendelssohn’s Hawaiian Serenaders. Grabham’s arpeggiated Fender Esquire (using ‘Nashville’ tuning) fuels the anguished ‘pinch to feel the pain’ ostinato. Touring in Dave Ball’s era, Robert’s Box lacked the concluding thirteen bars’ stirring guitar-solo.

Moonlighting from Pink

Floyd’s Dark Side marathon, Thomas (“working eighteen-hour days”)

exhausted sixteen-track capability on Grand Hotel’s extravagant

title-song: his mother’s Ealing choral society, orchestra recorded at AIR No 1,

and BJ’s twenty-two mandolins. He remembers Gary asking, “What have

you done to my song?”: yet Reid’s deftly-rhymed paean to excess demanded

such sumptuous embellishment. Union Chapel’s band-only version

blends the album’s grandeur – Brzezicki replicating BJ’s dramatic entry – with

characteristic Procol wit: Gary’s piano clowning, the gentle gypsy tango, the

irreverently-handled French backing-vocals.

Moonlighting from Pink

Floyd’s Dark Side marathon, Thomas (“working eighteen-hour days”)

exhausted sixteen-track capability on Grand Hotel’s extravagant

title-song: his mother’s Ealing choral society, orchestra recorded at AIR No 1,

and BJ’s twenty-two mandolins. He remembers Gary asking, “What have

you done to my song?”: yet Reid’s deftly-rhymed paean to excess demanded

such sumptuous embellishment. Union Chapel’s band-only version

blends the album’s grandeur – Brzezicki replicating BJ’s dramatic entry – with

characteristic Procol wit: Gary’s piano clowning, the gentle gypsy tango, the

irreverently-handled French backing-vocals.

‘Toujours l’Amour’ was a cocktail Procol encountered in Japan: the song is Keith’s “reflection on love in general”. Copping reckons the vinyl sounded “a bit soggy around the bottom end” – Thomas had fallen ill and had dictated the mix to Punter by telephone – but, live, “Alan Cartwright is an unsung hero, anchoring things down, while pushing them forward”. Procol’s Danish Toujours l’Amour (note Demis Roussos, scheduled to perform later, sizing up the venue!) sounds sensational sans studio wizardry: listen to Mick’s second solo! Between album and stage ‘give me a chance’ became ‘teach me to dance’, a rare lyrical mutation.

The same show yields Bringing Home the Bacon : eye-contact between piano and drums lets Procol take numerous, exciting risks with the opening cross-rhythms; Grabham’s Leslified solo has a reckless edge; Brooker attacks his Steinway, while Cartwright’s pick (most Harum bassists play finger-style) punishes his Fender Precision; Copping is regrettably out-of-shot. It was Procol’s second stab at this TV Special (the studio lost, then wiped, the previous month’s tape): hence, perhaps, such aggressive playing? Unruly vocalised riffs replace the album’s scarcely-audible ‘Pahene Recorder Ensemble’ (‘Harry Pahene’ was a professional pseudonym of Gary’s father); “Not being a singer, I did the best I could,” Alan confesses.

Cartwright “couldn’t hear a thing” at 1973’s Hollywood Bowl show, thanks to an asymmetrically-sited experimental PA. “With no foldback, no control over dynamics, it seemed like a lost cause.” Yet the LA Philharmonic’s leader knew the repertoire (“He kept saying, ‘Salty Dog... are we doing that?’”), and the choir was superb: Procol triumphed at “a very, very enjoyable concert” in Brooker’s words. TV Ceasar showcases their fearless guitarist (“We’d all like some of what Mickey had!” Copping laughs). Fireworks exploded and inflatable monsters erupted from the lake during Rule Britannia, Procol’s patriotic finale.

Grand Hotel’s novelty number was A Souvenir of London, the only track the band didn’t re-record when Grabham replaced Ball. Inspired by Oxford Street buskers and souvenir-vendors near AIR Studios, the single’s syphilitic undertow earnt a BBC ban, but it didn’t chart. At London’s 1972 Royal Philharmonic concert, Gary’s orchestration incorporated various traditional street-songs. This live take features Copping on banjo and Brooker on National guitar at Passaic, NJ (17 October 1975). Gary liked to wind up by proffering his cap for coins.

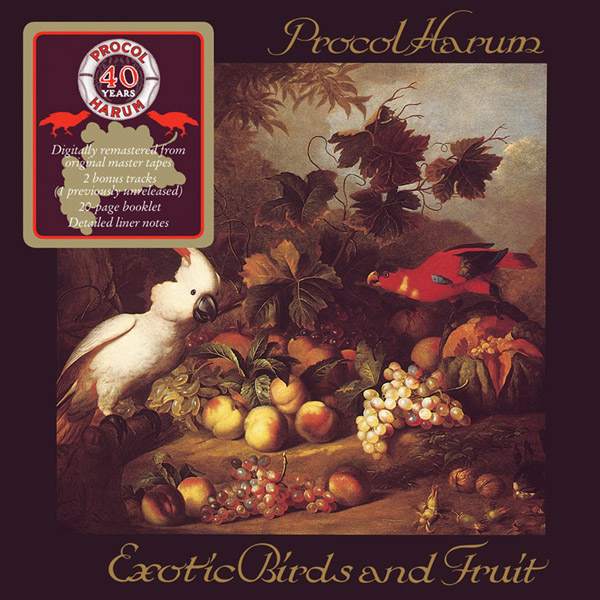

The 1974 Harum carried “increasing psychological weight, less spark”, Chris Thomas observes. Yet Copping loves “every note, every word, and the mighty production” of Exotic Birds and Fruit, and Grabham’s favourite Procol playing is his “licks in the bridge” of Beyond the Pale . Its punning title – adopted by the compendious www.procolharum.com – doesn’t cite the Jewish or Irish ‘Pales’, nor 1967’s megahit: ‘beyond the veil’ is what’s sung. Stage-weight hammering contributes an ‘anvil’ effect, and Wilson’s speeded-up mandolins provide a gypsy colouring alongside Copping’s banjo: “Procol hadn’t yet been to Poland or Romania,” says Chris, “but we’d certainly been watching Young Frankenstein.”

As Strong as Samson “aimed for the intensity of Blonde on Blonde”, according to Copping, “and didn’t fall far short”. BJ Cole (Grabham’s former Cochise band-mate, briefly poached from a neighbouring studio) contributes pedal-steel guitar; Mick strums a hired Martin D28 and solos on a Gretsch Viking. Reid’s Watergate-influenced words have lost no punch over thirty years, as Brooker notes at Union Chapel.

Few

Procol tunes mutate significantly, but in 1993 Gary was “bashing out chords” to

teach Samson

to newly-recruited organist Josh Phillips: “Brzezicki set up a groove, and the

upbeat version

was born.” This showcases Whitehorn’s flamboyantly-talking guitar, and

hosts a Johnny Nash fragment. Gary sports his MBE, bestowed that morning at

Buckingham Palace. “I’d

have been happier recording a DVD two nights before, in Zurich,” he admits;

it’s a demanding vocal for “one of the busiest days I’ve ever

known”.

Few

Procol tunes mutate significantly, but in 1993 Gary was “bashing out chords” to

teach Samson

to newly-recruited organist Josh Phillips: “Brzezicki set up a groove, and the

upbeat version

was born.” This showcases Whitehorn’s flamboyantly-talking guitar, and

hosts a Johnny Nash fragment. Gary sports his MBE, bestowed that morning at

Buckingham Palace. “I’d

have been happier recording a DVD two nights before, in Zurich,” he admits;

it’s a demanding vocal for “one of the busiest days I’ve ever

known”.

Brooker composed The Thin End of the Wedge following “a rare event, a terrible argument with my wife: Cm to F#m, as nasty as you can get!” These innovative harmonies, seething over Cartwright’s Fender Jazz bassline, impressed Robert Fripp, recording nearby (Crimson’s Reid-equivalent, offstage lyricist Pete Sinfield, later worked with Gary). “It’s hard enough, those chords and left hand... I didn’t write a melody,” jokes Brooker, whose track-record suggests a penchant for declaiming Keith’s words. BJ was unwell: “He’d have been all over the place, filling the gaps.” Regrettably Wedge is the one number that doesn’t survive from the band’s hard-hitting 1974 Danish TV Special.

Nothing But the Truth, a universally-admired single, failed to chart. “Faultless, magnificent,” insists Chris ‘Is it on, Tommy?’ Thomas. Yet Gary fears he’s “getting inspiration from myself”, recycling the Robert’s Box opening. “A bit noisy overall,” is his verdict; his Ledreborg arrangement pauses for breath following the middle eight (a Procol rarity, but specified in Reid’s typescript). Where Thomas overdubbed fleeting violins, Brooker writes expansively for choir and orchestra, quoting Psycho, and chromatically spicing already-tasty chords.

The same show supplies Butterfly Boys , an intriguing amalgam of Brooker’s assertive HP 109 piano, Whitehorn’s wailing Strat, and a witty, programmatic orchestration (originating on The Long Goodbye). Ledreborg’s spacious setting means Brzezicki’s dynamics aren’t cramped by the orchestra: “Fresh air is the best sound-proofing,” he explains. Phillips copes with an invisible Leslie, stowed below stage to achieve recording separation. Reid’s scathing lyric upset the ‘butterfly boys’ at Chrysalis Records, who’d “metamorphosed from management saviours into arriviste magnates” according to Copping. “There’s always bitching about managers,” Keith reflects. “In retrospect we had a pretty normal relationship.”

The Exotic Birds line-up rocks soulfully through The Idol despite its harmonic intricacy. “Having those complex chords flow so well shows Gary’s greatness as a writer,” says Copping. Grabham’s Leslified guitar (“not following chords, just sensing what blues notes go with non-blues harmonies”) expands on his fine recorded solo. Whitehorn later adopted various signature Grabham licks (“Fair enough,” laughs Mick, “I used plenty of Robin’s!”). Live, Procol shorten the album arrangement, which “needed a good prune” according to Thomas. His production ethic didn’t tackle song structures: “I was into painting, not scaffolding.”

Exotic

Birds concludes with New Lamps for Old, atypically-languorous and

organ-led, recorded – complete with dreamy Lucille-related playout – the

very night Brooker presented it at the studio. Reid’s opening quatrain “refers

specifically to a friend. I just followed that germ where it led, trusting the

subconscious”. Rock lyrics don’t come more densely suggestive than ‘The eye of

the needle, the loss of the thread’. Rarely performed, New Lamps for Old

was

recorded (22 March 1974) at Golders Green Hippodrome in London, for a BBC

broadcast. Live, Gary’s grand piano leads: as ever, he sings Keith’s ‘falsehood’

as ‘false head’!

Exotic

Birds concludes with New Lamps for Old, atypically-languorous and

organ-led, recorded – complete with dreamy Lucille-related playout – the

very night Brooker presented it at the studio. Reid’s opening quatrain “refers

specifically to a friend. I just followed that germ where it led, trusting the

subconscious”. Rock lyrics don’t come more densely suggestive than ‘The eye of

the needle, the loss of the thread’. Rarely performed, New Lamps for Old

was

recorded (22 March 1974) at Golders Green Hippodrome in London, for a BBC

broadcast. Live, Gary’s grand piano leads: as ever, he sings Keith’s ‘falsehood’

as ‘false head’!

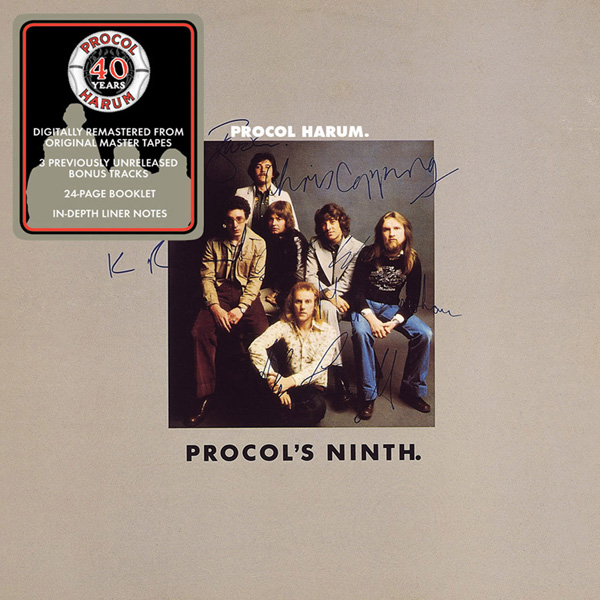

Procol’s Ninth was recorded at The Who’s Ramport Studios in Battersea (“right by the brewery... we watched an articulated lorry deliver their booze,” sighs Copping). It spawned a substantial hit in Pandora’s Box , which Procol had twice attempted to record since 1967: new producers Leiber and Stoller “altered the shape” according to Cartwright, “and kept adding things”: the intricate mix includes Brooker’s marimba and keyboard-strings, Grabham’s synth-like Les Paul layers, and – perhaps influenced by Nita Rossi’s 1965 Northern Soul classic, Untrue Unfaithful – a New York session-player on flute.

Gary’s commanding Bösendorfer grand on Fool’s Gold is reinforced by brass: “What were we, Chicago?” Grabham chuckles. Mick’s unconventionally-early guitar break suggests that these producers did work on ‘scaffolding’. Is the superbly-compact lyric confessional? “There’s a lot of me in these songs,” says Reid, “but I subscribe to the Harold Pinter school: it’s the iceberg: it’s as much about what you don’t see as what you do. I’m always looking for the right image to suggest something lurking around the corner, that taps into universal feelings as well.”

Taking the Time features Brooker’s classy, Elvis-influenced vocal and artful chord-progressions. Chris admires the “Duke Ellington-type orchestration”, and Mick the “stripped-down bluesy feel, very Leiber and Stoller”. Several Procol’s Ninth songs allude to Keith’s Home-era writing drought, but ‘taking notes and stealing quotes’, he says, “is what all writers do”, and doesn’t allude to any specific Procol ‘borrowings’, literary or musical.

Reid borrowed the title, The Unquiet Zone , from a TV documentary about World War I, and Brooker’s setting is suitably aggressive, using Hohner D6 clavinet, and American brass again (including David Sanborn): Gary supervised the US sessions. His singing is powerfully expressive and Procol – honed by extensive touring – absolutely sparkle, specially BJ’s supercharged drumming (otherwise highlighted on record only in a contrived, multi-tracked solo on 1971’s Power Failure). “He played how he felt,” Alan reminisces, “Unpredictable, keeping us on our toes! A lovely guy”.

Also in 1975 Procol recorded The Blue Danube, for Strauss’s 150th anniversary, invited by “The Fathers of Austria” as Brooker recalls. “Never daunted, always obliging,” he bought a piano reduction, to find it contained “about sixteen different tunes”! After six months’ live honing, Procol recorded it on-stage at Bournemouth Winter Gardens (17 March 1976): Muff Winwood mixed it for release (opposite Adagio di Albinoni) on their French instrumental single. The present track restores Winwood’s various excisions. The subtle ensemble playing is remarkable: “There’s a lot to get right,” Gary admits, “but so there is in Whaling Stories. BJ’s drumming is stupendous.”

2006’s Ledreborg contingent rousingly resurrects the grandiloquent Something Magic , Procol’s 1976 title-track. Josh Phillips’s Yamaha Motif synth replicates the record’s bright bell-like arpeggios (originating from the Farfisa VIP255 of Pete Solley, incoming organist when Copping returned to bass). Miami’s Mike Lewis contributed this cinematic arrangement, since Gary was busy scoring The Worm and the Tree. Brzezicki relishes Procol’s “blues-based music with interesting chord-structures”: in Something Magic Brooker rings frequent changes on over twenty chords – not counting inversions, suspensions or enharmonic equivalents – a challenge for all but the drummer!

Wizard Man,

however, uses just three chords, as befits a punk-era UK single (‘could well

kick the ghost of A Whiter Shade into the bucket’, as Melody Maker

punningly claimed in March 1977). “Solley’s a fine musician, lots of soul,” Gary

affirms. Pete feels his “Farfisa full organ, through a Leslie, frankly sounded

pretty good”. He’d ditched Procol’s trademark Hammond, vexing some “slightly

snobbish” fans: Fisher restores it at Copenhagen 2001

. Reid’s original, Beckettesque title

was Waiting for Christmas. Brooker’s countrified setting of his

complex imagery recalls The Crickets’ I Fought the Law: the wordless

vocal hook is a departure for Procol Harum.

Wizard Man,

however, uses just three chords, as befits a punk-era UK single (‘could well

kick the ghost of A Whiter Shade into the bucket’, as Melody Maker

punningly claimed in March 1977). “Solley’s a fine musician, lots of soul,” Gary

affirms. Pete feels his “Farfisa full organ, through a Leslie, frankly sounded

pretty good”. He’d ditched Procol’s trademark Hammond, vexing some “slightly

snobbish” fans: Fisher restores it at Copenhagen 2001

. Reid’s original, Beckettesque title

was Waiting for Christmas. Brooker’s countrified setting of his

complex imagery recalls The Crickets’ I Fought the Law: the wordless

vocal hook is a departure for Procol Harum.

One Eye on the Future, toured in 1976–77, was merely demoed during Miami’s Something Magic sessions. In 2001 the musical Procoholics of The Palers’ Band championed it: Procol returned to it after a thirty-year hiatus. They didn’t refer to the Miami demo, and the bridge developed somewhat differently: “We got it right this time,” Gary jokes. His attractive melody, spanning almost two octaves, carries unusually warm, nostalgic words. This performance (Schio, 30 November 2007) became the title-track of Procol’s download-only Italian live album, an innovation of current manager Chris Cooke.

Perpetual Motion shows how Procol Harum matured during a fourteen-year hibernation. Its poignant words glitter with allusions to other writers (three to Shakespeare) and self-quotation (Grand Hotel’s ‘silken sheets’, ‘slip and slide’): the complex, emotive setting too is classic Procol, Hammond-saturated as in Fisher’s salad days. One credit surprised purist fans: Matt Noble, the “guy up in Bronxville” whom Reid started writing with on migrating to New York. “His demos are so good, you’re making the record while you’re writing the song” says Keith: Noble became the Prodigal co-producer, his input meriting co-writer status.

Overturning established Harum protocol, the Prodigal tracks didn’t originate in live ensemble playing. “I remember thinking how strong the demos were,” Trower relates, “but I was disappointed with what I was able to contribute: rehearsing the songs as a band would have suited me better”. Bassist Dave Bronze concurs that “a lot had been done in New York before I was brought in”; Brzezicki’s drums were added only when it became clear that BJ Wilson would not be resuming his percussionist’s throne.

Yet the songs worked terrifically onstage. “Somewhat Talking Heads-inspired” in Reid’s view, Man with a Mission rides on Bronze’s five-string, self-designed for his 1991 Procol début on Johnny Carson’s show. Late-eighties’ Prodigal production-values surface only in Whitehorn’s Repliflex octave-divider (“I was into rack systems at that time, like everyone else”) and Fisher’s JX-8P synth and S1000 sampler. Keith’s lyric started life as a rap, in Gary’s No Stiletto Shoes; Procol references (‘eye on the future’, ‘method of access’) jostle with Miller and Waugh, and the ‘head full of air’ is Ronald Reagan’s!

Also from the One More Time album (Utrecht, 13 February 1992) comes the atmospheric The King of Hearts , a rare Procol ‘boy-meets-girl’ saga. Brooker does soaring like no other white soul vocalist: “That man can sing,” says Bronze, “It was pretty electric that night!” “Lovely receptive audience,” declares Geoff, who plays the PRS ‘Studio’ one-off made for him in his Bad Company days. “We'd been out solidly for weeks, got really good, yet tired enough not to care it was being recorded.”

The 1991 album

recording of (You Can’t) Turn Back the Page was lavishly overdubbed:

2007’s five-piece take

(Turin, 29 November) is no less powerfully nostalgic. The ‘hands of time’

(reversible in the youthful Homburg) now seem merciless; likewise the

middle-ten’s ‘Plea’s been denied’. Was the song about BJ? fans wondered.

But Gary never asked Keith for elucidation: “If you can’t figure it out, or get

your own picture, you’ve been working with the wrong bloke for forty years.”

The 1991 album

recording of (You Can’t) Turn Back the Page was lavishly overdubbed:

2007’s five-piece take

(Turin, 29 November) is no less powerfully nostalgic. The ‘hands of time’

(reversible in the youthful Homburg) now seem merciless; likewise the

middle-ten’s ‘Plea’s been denied’. Was the song about BJ? fans wondered.

But Gary never asked Keith for elucidation: “If you can’t figure it out, or get

your own picture, you’ve been working with the wrong bloke for forty years.”

Learn to Fly , recorded next night at Schio, “shows Procol can do rock-’n’-roll!” says Whitehorn, whose Vintage V6-Icon power-chords punctuate a chorus with Bach-derived harmonies (Well-Tempered Clavier, Book one, Prelude 21: “It so happens I can play that one,” Brooker explains). Unexpectedly, the verse’s two-chord thrash is Fisher’s contribution. Reid’s words, written to fit, are unashamedly demotic. “Becoming more direct, that’s a natural progression for a writer,” Keith suggests. “When you’re young, you discover new words and work them in, like young musicians trying to play all the notes. But, ultimately, the less the better. Sometimes the whole thing’s there in a title.”

A demo of Into the Flood, an early Prodigal-era song, made a European single bonus-track (Matt Noble on synth-bass and finger-padded Akai drums, Bobby Mayo and Tommy Eyre on guitar and organ). It has evolved greatly: Brooker orchestrated it on the train to Procol’s twenty-first anniversary Edmonton gigs, inserting a fiddle-punishing ‘hoedown’ by Mathias Weiss. The Ledreborg Flood additionally quotes Mozart’s Coronation Mass and some cheeky Beethoven: somehow Reid’s text (also used in Trower’s Gone Too Far) pulls the whole mélange together.

Procol’s self-referential proclivities flower in the hitherto-unreleased Last Train to Niagara , recorded at California’s Irvine Meadows Amphitheatre (18 September 1993). “Around the Prodigal Stranger time I decided to write an epic train journey,” says Keith, “to encompass points we’d visited in individual songs, and work in their themes”. Gary initially proposed a recurring motif (“that Em/Gm paradiddle, stolen from my own film music” (Ruud van Hemert’s Hitting the Fan, 1987)) linking entire songs, completely filling Procol’s 55-minute nightly allocation on Jethro Tull’s US tour. Rehearsal trimmed this unwieldy concatenation, until just ten thematic mementoes – some smoothly integrated, others “sticking out like a dog’s bollocks” – remain as we ‘flip across the dial’.

Despite rehearsing with Procol, Brzezicki had Big Country work to do; so Ian Wallace – ex-Crimson/Dylan, and a friend of Kellogs, by then the Harum manager – was initiated (“in a working tortilla factory, full of smoke, at Santa Fe” according to new-boy Pegg). Brooker improvised the film-noir introduction, thinking the lyric’s ‘twice removed from yesterday’ was a Mickey Spillane allusion, not a Trower song-title. After attempting to capture loco-noises at Grand Central (not actually the terminus for Niagara!) Gary resorted to library sound-effects (including an oil-rig) to reinforce Geoff’s Tom Anderson Strat racket on the train-wreck ending. According to the LA Times (18 September 1993) Niagara achieved Procol’s ‘old sense of a band exploring mysteries and taking a journey into the unknown’.

“I’ve never shirked Reidy’s challenging first lines,” laughs Gary about 2002’s So Far Behind , a long-neglected ‘Fitzrovia’ lyric. It was demoed for Something Magic, “altogether slower, with a rolling ‘two’ feel”; thereafter Procol toured a more boisterous version. Before the Well’s on Fire sessions, Chris Copping (now domiciled in Australia) sent Brooker a home-produced arrangement whose feel prompted Whitehorn “to get my wah-wah out, while Mark set up a pseudo-disco rhythm”.

Produced by Rafe

McKenna, at Roger Taylor’s Cosford Mill in Surrey, Procol reverted to recording

live; The Emperor’s New Clothes

was an exception, sung by Gary at the Steinway in an outbuilding, audibly

on Firework Night! (Since Procol’s return in 1991 Brooker has used digital

pianos, but “in my head I’m always playing a grand: it’s that sound I want”.)

Overdubs include Geoff’s Sid Poole Les Paul (“playing bluesy call-and-response

with Gary”) and Matt’s Zeta Uprite fretless five-string bass. What’s it about?

“Politicians everywhere” is Keith’s succinct summary.

Produced by Rafe

McKenna, at Roger Taylor’s Cosford Mill in Surrey, Procol reverted to recording

live; The Emperor’s New Clothes

was an exception, sung by Gary at the Steinway in an outbuilding, audibly

on Firework Night! (Since Procol’s return in 1991 Brooker has used digital

pianos, but “in my head I’m always playing a grand: it’s that sound I want”.)

Overdubs include Geoff’s Sid Poole Les Paul (“playing bluesy call-and-response

with Gary”) and Matt’s Zeta Uprite fretless five-string bass. What’s it about?

“Politicians everywhere” is Keith’s succinct summary.

Brooker had been developing An Old English Dream (working titles included A Christmas Song and Ten Thousand Souls) since the late 1990s, adapting it to Reid’s long lines, closely-modelled on WH Auden’s Refugee Blues. The original melody became Gary’s piano solo, played at Union Chapel on his workhorse Roland RD600, encarcased in the ‘faux grand’ built by former road-manager Barry Sinclair. “An inspirational musician to work with,” says Brzezicki of ‘The Commander’. “There’s nobody like him.”

“It’s years since anyone else in Procol made a strong writing connection,” Brooker reflects, “though Geoff has often been ‘the man’: his slide guitar on The VIP Room is spectacular”. At the Isle of Wight Josh plays with Copping-like verve (“my favourite Procol organist, apart from myself!”) and a fresh generation falls under the Brooker/Reid spell. “We’ll always be a band that reacts,” Gary continues. “We’ve had some people do exactly the same from one century to the next, great original ideas, but playing safe. I’m happiest when I hear human emotions going into Procol Harum music.” Amen to that!

A box-set retrospective is not an epitaph. These notes were completed on the Ides of March 2009, the very day Procol Harum returned to the studio after a fifteen-month sabbatical. A worldwide audience waits to hear how the forthcoming Brooker/Reid material will continue the story of this remarkable band.

Roland Clare, Bristol © 2009

Many thanks to Dave Ball, Dave Bronze, Gary Brooker MBE, Mark Brzezicki, Alan Cartwright, Chris Cooke, Chris Copping, Geoff Dunn, Mick Grabham, John ‘Kellogs’ Kalinowski, Josh Phillips, Matt Pegg, Harry Pitch, Simon Posthuma, Keith Reid, Pete Solley, Chris Thomas, Robin Trower and Geoff Whitehorn; all conversations quoted above took place during the winter of 2008–09, specially for this project.