Procol

Harum

Beyond

|

|

|

PH on stage | PH on record | PH in print | BtP features | What's new | Interact with BtP | For sale | Site search | Home |

|

'Style

Council’ : Procol Harum and prog rock

Barry Cleveland in Guitar Player, March 2005

What exactly is progressive rock? That depends on whom you ask. Enthusiasts laud the music’s ambitious compositional scope, virtuosic instrumental excursions, literary lyrics, and overall sonic majesty, while detractors decry its overarching pretentiousness, interminable solos, self-absorbed lyrics, and overblown arrangements. In fact, dozens of bands from the ’60s and ’70s are routinely lumped together under the progressive rock banner, and, whatever one makes of them, their styles often differ dramatically. Add to that the hundreds of “neo-progressive” and “progressive metal” bands that have followed in their wake, and a comprehensive definition of the music remains as elusive as an acid vision.

One thing, however, is certain: Many of the artists hoped to legitimize rock as a serious art form by elevating it to a level of sophistication equal to that of jazz and classical music, and to that end they appropriated instrumentation and compositional elements from both. But other influences entered the mix as well, including American and British Isles folk, psychedelia, opera, and electronic. Bands specifically cited as progressive rock precursors (and sometimes considered to be progressive bands themselves) include England’s Pink Floyd, Traffic, and Deep Purple; and America’s Spirit, Magic Band, and Mothers of Invention; as well as the early British “Canterbury Scene” bands, such as the Wilde Flowers, Soft Machine, Caravan, and Gong; and Miles Davis’ “electric period” bands.

Though progressive rockers appeared worldwide, particularly in Europe, for the purposes of this brief overview we’ll consider the music as a British phenomenon occurring between 1968 and 1976, taking a few of the most influential artists as examples.

Progressive Progenitors

In mid 1967, Procol Harum—a speculative band assembled primarily by lyricist Keith Reid, vocalist/pianist Gary Brooker, and organist Matthew Fisher—had a huge hit with “A Whiter Shade of Pale,” a haunting song based on a Bach Air, that successfully fused rock instrumentation with elements of classical composition. The band’s lineup shifted soon thereafter—most significantly, guitarist Ray Royer was replaced by powerhouse blues-rocker Robin Trower—but “Whiter” demonstrated the commercial viability of blending rock and classical sensibilities.

Several months later, British Decca commissioned a floundering R&B band called the Moody Blues to record an entire album with a symphony orchestra. Days of Future Passed spawned two hit singles and was a runaway success. Hoping to further capitalize on the “rock band with orchestra” formula in a more cost-effective way, the band began using a Mellotron to emulate orchestral sounds. The Mellotron (a tape-based keyboard “sampler” introduced in 1965) had been used on the Beatles’ “Strawberry Fields Forever” and the Rolling Stones’ “2000 Light Years From Home” earlier that year, but the Moody Blues built their entire sound around the instrument.

Another popular R&B band that got saddled with an orchestra in 1967 was the Pretty Things. The resulting album, Emotions, contained progressive tendencies that would fully manifest in S.F. Sorrow, an ill-fated masterpiece recorded later that year. Sorrow was both a psychedelic “rock opera”—predating and reportedly inspiring Tommy—and a concept album featuring Mellotron, elaborate special effects, and other progressivisms.

Progressive Superstars

While the Moody Blues and the Pretty Things were having their songs scored for orchestra, Keith Emerson and the Nice were performing selections from the classical repertoire arranged for rock band. Emerson mitigated the seriousness by dressing in flashy outfits, hurling knives around the stage, and humping his Hammond before setting it ablaze. The band released three influential albums before Emerson left to form the “supergroup” Emerson, Lake & Palmer with ex-King Crimson bassist/vocalist Greg Lake and ex-Atomic Rooster drummer Carl Palmer. (Jimi Hendrix expressed interest in joining before his tragic death.)

The supergroup sported a super-sized setup to match: Towering stacks of Moog modules atop a rotating grand piano and Hammond L100 organ, a wall of Hiwatt bass amps, and a colossal drum kit. And all that gear produced a big sound—whether used for sensitive pop ballads, angular sci-fi extravaganzas, or grandiose renditions of works by Copland and Mussorgsky—and at the peak of their career they had sold over 30 million records and packed arenas throughout the world.

Founded in 1968, the original lineup of Yes centered on singer Jon Anderson and bassist Chris Squire’s high vocal harmonies, Anderson’s dreamy lyrics, Squire’s punchy Rickenbacker lines, and Bill Bruford’s economical yet dynamic drumming. Guitarist Peter Banks and organist Tony Kaye added jazzy R&B and psychedelic flavors. On 1970’s Time and a Word, Yes became a de facto symphonic rock band by grafting a small orchestra onto their songs—but it was 1971’s The Yes Album that signaled the group’s transition to truly progressive status. Steve Howe replaced Banks on guitar, upping the stylistic ante with shades of Montgomery, McLaughlin, and Atkins. Howe’s tones—elicited from a huge variety of guitars including Gibson fatbacks and lap steels, pumped through Fender stacks via wah, volume, fuzz, and echo pedals—were in turns smooth, chunky, squawky, and searing. When Rick Wakeman replaced Kaye a year later, bringing with him a Mellotron and a more classical orientation, the process was complete. Fragile and Close to the Edge introduced increasingly ambitious and lengthy compositions, culminating in the four 20-minuteish-long songs on the double-LP Tales From Topographic Oceans. On 1974’s Relayer, Patrick Moraz replaced Wakeman, bringing a jazz-rock fusion flavor to the final album from the group’s most fruitful period.

Early in 1969, Genesis released From Genesis to Revelation, an album of quirky pop songs performed by vocalist Peter Gabriel, keyboardist Tony Banks, guitarist Anthony Phillips, bassist/guitarist Michael Rutherford, and drummer John Silver—with a string section added as an afterthought to make them sound more like the Moody Blues. That album, and 1970’s Trespass, featured intricately layered 12-string and nylon acoustics, electric leads, acoustic piano, organ, and touches of Mellotron and flute. On 1971’s Nursery Cryme, Steve Hackett replaced Phillips on guitar, bringing a heavier and more electric sound to the group. Hackett’s Les Paul/Hiwatt combo, augmented by a bevy of pedals and a dysfunctional EMS Synthi Hi-Fli guitar synth, injected richly textured chord washes and echo-y, Tone-Bender-sustained lead lines [some of them tapped, see Play sidebar] into the ensemble compositions.

The new lineup, which also included drummer Phil Collins, staged elaborate theatrical presentations, with Gabriel changing costumes for each of their ever-more complex and epic-length songs—songs that typically dealt with mythological and literary themes. That trend continued with Foxtrot in 1972, and Selling England by the Pound the following year. Genesis’ reached its creative peak in 1974, with The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway, a musical and theatrical tour-de-force combining staggeringly sophisticated musical arrangements, phantasmagorical lyrics, and a full-blown multimedia stage presentation. Gabriel departed after touring The Lamb, ending Genesis’ creative heyday.

Jethro Tull began in 1968 as a jazzy blues-folk-rock ensemble led by charismatic flautist/vocalist/guitarist Ian Anderson, who wore an old raincoat and played flute while standing on one leg. After releasing its first album, This Was, the band replaced its bluesy guitarist, Mick Abrahams, with Martin Barre, whose immense riffs and tasteful, compact solos became staples of Tull’s increasingly hard-rock sound. (Future Black Sabbath founder Tony Iommi and ex-Nice guitarist Davy O’List each held the gig briefly before Barre, illustrating the fluidity of the music scene at that time). Throughout the ’70s, the group’s compositions grew ever longer and more elaborate, which didn’t keep them from scoring 11 gold and five platinum albums.

Creative Heights

Some of progressive rock’s most innovative and accomplished groups never achieved superstardom, though their music profoundly affected that of their peers, and the rock world in general. Of these bands, three stand uniquely apart.

The harmonic invention and sheer technical virtuosity displayed on King Crimson’s 1969 debut, In the Court of the Crimson King, were unprecedented in rock, and the guitar work alone spawned leagues of imitators. Robert Fripp’s tone was at times delicate and nuanced, at others devastatingly distorted—and when he combined rapid finger vibrato with fuzz and tape echo, his ’57 Les Paul Custom sang with electrifying and seemingly infinite sustain. Combined with Ian McDonald’s layered reeds, woodwinds, and keyboards; Michael Giles’ innovative drumming; Greg Lake’s commanding bass; and Peter Sinfield’s impressionistic lyrics, the result was an “uncanny masterpiece,” as Pete Townshend referred to it. The original lineup had disbanded by year’s end, though Fripp and Sinfield assembled various combinations of musicians for three more albums, including the hallucinogenic Lizard (featuring a cameo vocal by Jon Anderson), and the neo-classical Islands.

In late 1972, Fripp parted ways with Sinfield and reformed King Crimson with violinist David Cross, bassist John Wetton, percussionist Jamie Muir, and drummer Bill Bruford. The group’s initial release, Larks Tongues in Aspic, combined wildly dynamic and experimental works in 7/8, 13/8, and other odd time signatures, with hauntingly beautiful songs featuring sweet violin melodies, sumptuous guitar, and Mellotron. Fripp’s guitar became increasingly prominent on the next two records, Starless & Bible Black and Red, after first Muir and then Cross, exited the band. The mind-bending crosspicking on “Fracture” and “Starless,” and the layered metal majesty of the arpeggiated chords on “Fallen Angel,” extended Fripp’s singular stylistic domain. Live, the band improvised extensively, channeling music of a decidedly cosmic character. That incarnation of the band ceased performing in 1975.

Formed in 1968, Van Der Graaf Generator used dramatic tempo and time changes, unusual reed and keyboard colorations, and creative effects to create its oddly compelling music. Led by guitarist Peter Hammill, whose existential lyrics and tortured vocals helped further distinguish the group, Van Der Graaf was perhaps the most iconoclastic of all the progressive rock bands. Hammill dissolved the group after the 1971 release of its fourth album, Pawn Hearts (featuring contributions by Fripp), considered by many to be the band’s masterpiece. The group reformed four years later, releasing three albums of slightly less complex music showcasing Hammill’s narrative lyrics.

Founded in 1969 by brothers Derek, Ray, and Phil Shulman, Gentle Giant brought a somewhat medieval feel to its amalgam of jazz, classical, and rock. The Shulmans—who between them played bass, keyboards, violin, guitar, percussion, vibraphone, and saxophone—were also accomplished singers, and along with keyboardist Kerry Minnear and guitarist Gary Green, they crafted multi-part vocal arrangements to accompany their complex instrumental and rhythmic structures. The group released seven albums between 1970’s Gentle Giant and 1975’s Free Hand, generally evolving to a more compact and rockier sound, but never succeeding commercially. They continued to perform and record until 1980.

R.I.P.

R.I.P.

By 1976, the movement that had sought to elevate rock beyond mere rock and roll was being mercilessly ridiculed by the press and the burgeoning punk movement for having gone too far. Many progressive rock artists continued working either under their original band names or in new combinations, and near relatives such as neo-progressive metal emerged during the intervening decades – but the creative energy that originally informed progressive rock had run its course by the end of the '70s.

|

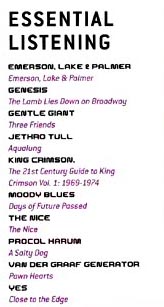

ESSENTIAL LISTENING |

||

|

EMERSON, LAKE & PALMER Emerson, Lake & Palmer |

GENESIS The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway |

GENTLE GIANT Three Friends |

|

JETHRO TULL Aqualung |

KING CRIMSON The 21st Century Guide to King Crimson Vol. I: 1969-1974 |

MOODY BLUES Days of Future Passed |

|

THE NICE The Nice |

PROCOL HARUM A Salty Dog |

VAN DER GRAAF GENERATOR Pawn Hearts |

|

YES |

|

|

Thanks, Jill, for the original typing

|

PH on stage | PH on record | PH in print | BtP features | What's new | Interact with BtP | For sale | Site search | Home |