Procol HarumBeyond

|

|

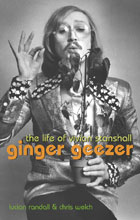

Please treat these brief excerpts ... quoted by kind permission of Lucian Randall ... as an unashamed advertisement for this admirable (if controversial) rock biography of an hilarious, influential and ultimately tragic figure from the British Rock / Art scene. Ginger Geezer tells the story of the turbulent and inspired life of Vivian Stanshall, best to known to many as the front man of the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band, who also collaborated with Mike Oldfield, Steve Winwood, and Keith Reid. It was published by Fourth Estate in 2001 [hardback ISBN 1-84115-678-7] and in paperback in October 2002 [ISBN: 1-84115-679-5].

Order from Amazon by clicking direct on one or other of these links: Hardback edition, Paperback edition

About Stanshall's writing collaboration with Keith Reid [pages 176-177]

At home, rattling around a house full of Bonzo props and weirdness on his own, Vivian thought up some more schemes to divert himself. He went up to town to play darts with the Melody Maker team, playing a side fielded by the Strawbs. He turned up dressed as a dart, wearing dart flights on his trousers, a spiked helmet and declaring he would play by lowering his head and running at the board. The Strawbs entirely failed to be amused by this, or by the state-of-the-art equipment Vivian had constructed to foil their efforts, such as shaped wire coat hangers which he claimed were sights to improve his aim.

He found a more appreciative audience when Procol Harum, best known for the

hit A Whiter Shade of Pale, asked him to support them on their farewell

tour [sic] of Britain in January and February 1976.

He put a band together, called Vivarium, but billed as Vivaria. It featured

Bubbles White on guitar, Dick Parry on tenor sax, and Pete Moss on bass and

piano. It was not a rock band. 'No, I wouldn't say that: an illustrative band,'

said Vivian. 'Played a few oldies.' He also wrote a song with Harum's lyricist,

Keith Reid, which took its inspiration from one of Vivian's many newspaper

cuttings, this one concerning an unfortunate family named the Browns.

Vivian and Keith 'knocked up a song about the Browns that my gang and his gang could thrash through'. Although Vivian rarely took a song directly from his Book of Madness cuttings, the tragic tale of the Browns had him guffawing out loud as he read it to Procol's writer. Vivian was sufficiently amused by the story to keep hold of the article and read it to visitors later in the year. With the drama that only a local paper can supply, the couple next door to the Browns are quoted: 'We'd been getting on quite well with the Browns. After our lavatory became completely blocked, I called the council. They were around in next to no time in their lorry. They went into No 40, our house, and inserted their biggest pump into our convenience.

'"One of the council operatives switched it on. There was a tremendous rumble. Janet, my five-year-old, thought it was thunder. The rumble was followed by a tremendous whoosh. I nipped upstairs and flushed the convenience. It was working perfectly. No sooner had the operatives vanished when I saw June Brown from No. 42 coming up the garden path. She was hysterical. Apparently, when the pump began to work, instead of sucking, it blew, and the whole of Mrs Brown's bedroom suite was covered with effluvia."' Vivian thought the choice of 'effluvia' to describe the devastating substance was particularly amusing. The paper goes on to record the reaction of the Browns themselves: "The council are to blame," said Bob Brown. "We are camping out at June's parents. Our house is ruined. It's everywhere. The ceilings are in danger of collapsing, the lavatory pan has blown into the spare bedroom and the TV is all clogged up."' The result of this was a number performed live - The Browns. An apt title indeed. Vivian also performed other tracks and an accompanying set with his own band.

[Read a Procol / Stanshall setlist from this tour, and see other non-Procol collaborations of Keith Reid's]

Stanshall wreaks havoc with BJ's drums [pages 177-179]

The tour followed the pattern Vivian set when he played with Grimms. He hit a peak around the second or third show and by the time they played their last night in Oxford, the anxiety of performing, compounded by drink and Valium and made worse by the emotional fallout of his split with Monica [his first wife], overcame him. Disaster struck at a gig in Birmingham on 28 February [sic ... should be January?]. His band were doing the old stuck-record routine which had been such a winner in the Bonzos. While they mimed, he was supposed to leap off the stage and kick it, and the band would jump forward into the song again. That night, he'd been wandering around the stage in a long nightshirt and sandals.

'I jumped off the stage for a gag; he said, 'and they had carpets.' Vivian slipped on the carpet, tore a ligament and dislocated his left leg. To make matters worse, he earlier 'told the bloke on the spot [light], whatever I do - because I like jumping off and running into the audience - whatever you do, follow me. So I put my arms around the bloke in the front row and went, "Ohhhhh, ohhh, ohhh!" Poor man. With the spot beaming down ...'

'The audience thought it was wonderful; recalls Pete Moss. 'Then I realized he really had hurt himself. We stopped playing.' Vivian's saxophonist Dick Parry called out, 'Is there a doctor in the house?' Once more, the audience cheered at the crazy humour of this Bonzo man. 'We got him back up on stage and finished the night; explains Pete, 'but he was in a terrible state' He told Vivian to check himself into the Royal Free Hospital when he was still in pain the next morning. Two days went by and Pete did not hear from him.

Eventually there was the usual, chatty telephone call. 'Hi, amigo,' breezed Vivian. 'I've sorted this whole thing out. I've had acupuncture.' How exactly this was supposed to help a severely damaged shin was unclear. Pete was exasperated. 'No, you've got to go to a hospital,' he insisted. 'This is the last night of the tour. Everybody is coming to see you.' But that only put more pressure on Vivian.

'I'm coming down to see you,' he told Pete. 'There's only one problem. I can't walk.' Pete told him to improvise - get a broom for a crutch or something.

'That's a good idea, amigo. I'll see you later.' Grabbing an axe, Vivian beetled down to the bottom of his garden and chopped down a tree - there was the instant crutch, albeit not quite what Pete had in mind. With a football boot and sock on one end, he hobbled off in the general direction of Pete's place in Ossulton Way. But he got the house wrong. The door he knocked on was opened by a sixty year-old Jewish lady who was somewhat alarmed to be greeted by a wild-eyed giant reeking of rum, wearing octagonal glasses, a knotted red beard and a nightshirt covered in moons and stars.

The figure, leaning on a big crutch made out of a tree with a football boot

on the end, roared, 'Where's Pete?' His bellow induced a scream of terror, at

which point Vivian collapsed on top of the unfortunate woman. Somehow he managed

to get up and stagger off, while she was left in a heap. Across Ossulton Way was

the house of Dean Ford, lead singer with the Marmalade. He saw the whole thing

and was doubled up, crying with laughter. When Vivian eventually turned up, Pete

promptly confiscated the bottle his friend was clutching and refused to accede

to his demands for its return on their arrival at the gig. 'I knew he was going

to blow it.' At the venue, Vivian simply paid someone else 10 pounds to get him

a bottle of whisky. With time to explore the venue, Vivian discovered there was

a trapdoor in the stage. Immediately, he decided he wanted to come up through

the hatch rather than come in from one of the wings. He promptly stumped up

another bribe for someone to let him try it. When show time came, the band could

not find him and eventually started The Intro and the Outro without their

star. This went on for some minutes and Moss began desperately shouting at the

roadies: 'Where is he?'

'He's coming, he's coming' He was. A hole in the floor appeared beside Pete, as the trapdoor swung open and up shot Vivian Stanshall on to the stage, complete with improvised tree-crutch. And facing the wrong way. 'Where am?' he boomed. 'Turn round, Vivian' hissed Pete. The singer tripped over his crutch with the football boot and crashed into Procol Harum's drums, completely demolishing the entire kit, half of which fell into the orchestra pit. 'He never really got anything right that night,' adds Pete, 'and it was the last tour we ever did.'

[BJ's drums were downstage left, of course. Read an illustrated review of a Procol / Stanshall gig]

On the road with Keith Reid and the Hells' Angels [page 179]

The musicians drove back in a coach down the M1. They stopped off at a Blue Boar service station and went into the restaurant. As if they had been waiting just for them on cue, a gang of Hells' Angels were lounging around. Five musicians went in, including Keith Reid. The gang only had to look at Vivian to find all the excuse they needed to start trouble. And Vivian, ever keen to play the macho man, never even needed an excuse. He leapt on to a table. 'Come on,' he yelled, 'I'll take on the lot of you!' Even the band's driver, no pint-sized wimp, was shouting, 'Get down from there!' They all bolted for the coach, with the Angels in hot pursuit and Vivian shouting to his friend, 'Come on Pete - you and me!'

About Southend, cradle of Procol Harum, where Stanshall grew up [pages 2 - 3]

It was in a Great British seaside resort that Vivian spent most of his

childhood. Southend-on-Sea is a cheeky, presumptuous sort of place. For a start,

it is some thirty-five miles to the east of London, rather than south. It is

situated on the Thames Estuary; not quite the sea. It does have a famous funfair

called the Kursaal and a mile-and-a-quarter pier, the world's longest. Gaily

festooning the seafront are the famous illuminations, signalling Southend's

status as an alternative to the drab, city streets of the capital. It certainly

performed this function for many deprived London families in the 1950s. After a

slow and tedious journey by steam train, thousands of eager holiday-makers

spilled out of the station and headed for the front in search of dodgem cars,

slot machines, deckchairs, hot dogs, jellied eels, cockles, tea and a game of

bingo. The highlight was a trip on the pier railway or a heart-stopping ride on

the water chute at the Kursaal.

London kids thought of 'Sarfend' as a sort of paradise, a Never-Never Land where time stood still and everyone lived on a diet of sweets, candy and hot doughnuts. It was difficult to imagine anyone actually living and working in such a pleasurable environment.

The small but busy town grew into an urban sprawl during the post-war years. In the process it merged with its older neighbours like Leigh-on-Sea. In this cluttered coastal conurbation Vivian Stanshall grew up in the 1950s with his mother, father and younger brother. Leigh-on-Sea isn't quite the romantic artist's birthplace that Dublin, Paris or New York are, though actor Steven Berkoff was attracted to the area, featuring the mighty Kursaal amusement park in his early autobiographical play, East, as a place of escape and excitement. For a youngster who lived in the town all year round, it was the soulless 'Concreton' alluded to in Vivian's later tales of Sir Henry Rawlinson. If nothing else, the years there inculcated in Vivian a love of seafood, English seaside resorts and Cockney slang, habits and tastes.

Leigh-on-Sea was actually the remnants of an old fishing and smuggling village, which was well established when upstart Southend was still a hamlet. It was a place where you could still find cockle boats and sheds, sailors' inns and clapboard cottages ...

Growing up in Southend [page 14]

Southend-on-Sea was an adventure playground outside work and school hours. It was where a youngster could roam the streets as a teddy boy. In the mid-1950s, British boys and girls thrilled to the new sounds from the States, together with the paraphernalia of being a teenager: B-movies, horror comics, pop records and trendy fashions. Where once they had jived to Ted Heath and his Orchestra, they now learned to rock'n'roll to Bill Haley and the Comets, Elvis Presley, Gene Vincent and Little Richard. Aged just eleven when rock'n'roll first broke ... [Stanshall, born 1943] ... was too young to be in with the gangs. He bought his first pop records instead: Rock with the Caveman by Tommy Steele and Giannina Mia by Gracie Fields.

English kids adopted the clothes, slang and violent habits of teddy boys, taking their name from the Edwardian styles that became fashionable at the start of the decade: drape jackets with velvet collars and thick-soled shoes nicknamed brothel creepers. On the back cover of Stanshall's 1981 album Teddy Boys Don't Knit, there is a black-and-white snapshot of him as a youngster, sitting sprawled with his mates on a bench in the street. They loaf in the maliciously indolent way that only teenage boys can, under a Southend police noticeboard. A 'Keep Britain Tidy' poster depicts a huge finger pointing directly at Stanshall's head. Clad in blue suede shoes and drainpipe jeans and sporting a Tony Curtis hairstyle, he sits and grins, sporting the kind of expression that members of the officer class might have interpreted as dumb insolence.

Order from Amazon by clicking direct on one or other of these links: Hardback edition, Paperback edition